Around one and a half months have passed since the lockdown started to be lifted in Kyrgyzstan and the consequences of this decision are already cause for serious concern. Since the start of June, the number of registered COVID-19 infections in the country has more than quadrupled. Hospitals are full of patients suffering from a pneumonia wave that is almost certainly related to the coronavirus. COVID-19 infections have been detected in parliament and among members of the government. Kyrgyz president Sooronbay Jeenbekov was unable to take part in Moscow’s Victor Day Parade on 24 June after two members of his delegation tested positive for the virus. And since then, former president Almazbek Atambaev, recently sentenced to 11 years and two months in prison, has been hospitalised with double pneumonia.

Caught between poverty and illness

Kyrgyzstan is both a very free country and a very poor one. In the three decades since independence, the Kyrgyz people has managed to topple its first two presidents and a few days ago the third, Almazbek Atambaev, was sentenced to 11 years and two months in prison. In comparison with other countries in Central Asia and the wider post-Soviet space, the local press, politics and civil society in Kyrgyzstan enjoy an almost unlimited freedom. The authorities, it is true, do mount sporadic attempts to reign this freedom in by the use of rather severe tools – such as the recently-adopted controversial law “On the manipulation of information” that effectively introduces internet censorship. But no one stopped the Kyrgyz public from actively contesting this law, among other things through major street protests.

At the same time, the chronic budget deficit in Kyrgyzstan is a factor whose influence is felt practically everywhere in the country, not least in the healthcare system. As of autumn 2019, the monthly wage for a doctor with more than 30 years of experience, and who has obtained the maximum number of points for good work, came to just 30,000 Kyrgyz soms ($428 dollars). And this is already three times what it was before a recent wage hike. Such financial prospects necessarily lead to a deficit of qualified staff. Things are not much better when it comes to resources and equipment. The shortage of ambulances is felt keenly even in Bishkek, while remote rural areas can go for years without even a single emergency services vehicle or the fuel required to keep it running. Since independence, even functioning morgue refrigerators have turned into something of a luxury, far from a given at all times.

As soon as the global COVID-19 pandemic got underway, it was clear that if the situation were to slip out of control in Kyrgyzstan, the local healthcare system would not be able to hold out for long. One could, of course, hope for foreign grants, and these did indeed start to come in. The present situation, however, poses a major problem not just for Kyrgyzstan but for the whole world, including donor countries themselves, and relying on truly comprehensive assistance was simply not an option. In addition to all this, we should not forget about the Kyrgyz love for freedom. The Kyrgyz public looks with an agitated eye on any kind of restrictions, including lockdown measures. As long as it does not truly believe in the danger posed by the new virus, forcing it to observe safety measures was always going to be a tricky affair. On the other hand, a full awareness of approaching danger can provoke panic, which itself never leads to anything good.

The authorities initially resolved to hold back the spread of the epidemic at any price. On 22 March – four days after the first cases were detected in Kyrgyzstan – a lower-level state of emergency (chrezvychaynaya situatsiya – “emergency situation”) was declared across the nation. On 25 March a high-level state of emergency (chrezvychaynoe polozhenie – “emergency state”) was introduced in Bishkek and other major towns, plus several rural districts. Authority was handed over to special executive committees headed by officials from the ministry of internal affairs. Only a limited number of branches of the economy deemed essential were permitted to operate. The majority of citizens were required to remain in their homes. Even trips to a pharmacy and nearby stores were strictly regulated.

And this approach worked. It was not until 10 May that the number of Kyrgyz coronavirus cases reached the milestone of one thousand infections (by way of comparison, in Moscow alone 12,700 people had already tested positive for the virus). The list of fatalities, too, rarely had to be updated – by 11 May it included only 12 individuals. Quickly, however, the “poverty factor” came into play. Many Kyrgyz not only do not have any savings worth mentioning, they literally depend on their daily earnings to survive. If a man works as a taxi driver or market trader then each evening he can buy food for himself and his family only with the money he has made that same day. For such people, skipping work for a month or more is an impermissible luxury. Civil society organisations and the government helped those in need by distributing food parcels, but this only brought a minor improvement in their situation. Finally, their very success in holding back the epidemic unexpectedly turned against the official virus fighters themselves. The average Kyrgyz citizen simply did not understand why he should continue to sit at home all day and survive on spaghetti from humanitarian aid parcels simply on account of a thousand poorly patients and a dozen dead.

Businesses too started to suffer. Just like ordinary citizens, Kyrgyz businessmen rarely have the luxury of a financial “cushion” allowing them to sit out a temporary standstill unperturbed. In addition to this, employers felt obliged to dig out the funds needed to at least partially support their employees. Nor did the authorities help them by, for instance, suspending taxes. Business owners were merely exempted from fines for late payment of taxes until 1 June, and given the right to request the deferral of tax payments until 1 October. But at the end of this period they were still going to have to pay in full all the same. On top of this there were rent fees, utility charges... It quickly became clear that if the situation continued for much longer then there would simply be no one left to contribute taxes to the meagre Kyrgyz state budget. Unless, of course, they planned to fill it with the debts accumulated by a mass of bankrupt firms.

The price of freedom

And so on 11 May the full-blown state of emergency in Bishkek and elsewhere was lifted. The authorities stressed that in these areas, as in the rest of the country, the lesser “emergency situation” would remain in place. Few people, however, had much time for such subtleties. The main agenda in the Kyrgyz media became the resurrection of the economy and overcoming the lingering consequences of the lockdown. Few people were bothered by news about the coronavirus itself... At least for now.

On 10 June, the first infection was confirmed in the Talas region – the only remaining region in Kyrgyzstan that had thus far remained free of the virus. And then, in the second half of June, the number of infections throughout the country started to rise sharply. By the end of June, the number of confirmed infections had grown by 4.6 times since the start of the month. For comparison, over the whole of May they grew by 1.3 times, and in April 1.6. The number of deaths, too, suddenly began to increase at a worrying rate. Not long ago, the health ministry was reporting one or two deaths far from every day. Now such announcements have become a daily affair, and by 29 June the list has grown to 50 individuals. (78 as of 4 July, with a record 10 deaths reported on 3 July – ed.).

At the same time, reports had started to appear in the media of large numbers of people suffering from pneumonia. On 25 June the head doctor of Bishkek’s Emergency Medical Centre, Iskender Shayakhmetov, stated that in one day alone on 24 June, 57 such patients had been registered, although there are normally no such cases in the summer at all. “These are also severe pneumonia cases, atypical ones, and, importantly, they can’t be picked up using a stethoscope but are only visible by X-ray,” he stressed. Shayakhmetov added that doctors were sometimes seeing a clear clinical picture of COVID-19 alongside negative PCR test results.

Other doctors interviewed in the media also argued that the majority of such pneumonia cases were being caused by the coronavirus. If this is indeed the case then Kyrgyzstan currently has not just 7,094 cases of the illness as is shown in the official statistics (updated on 4 July – ed.), but far, far more. The fatality statistics would also need to be updated – because people are dying from this strange “summer pneumonia” too. One of them is 38-year-old head of the Counter Narcotics Service Oleg Zapolskiy. Another policeman, 37-year-old Berdibay Elakunov, also ended up in hospital with pneumonia. He himself was convinced that he had caught the coronavirus and recorded a video message with a stark warning for his fellow citizens: “This is a terrible illness, I can tell you. So please be careful, wear face masks. The National Hospital is full of patients, others still are being refused admission. The ambulance services just keep on bringing people. The situation in the city right now is awful.”

On 29 June Elakunov died. The same day, Health Minister Sabirjan Abdikarimov announced that 54 Kyrgyz citizens in total had died of pneumonia without a positive coronavirus diagnosis since March. “We are currently recording pneumonia patients in a separate category,” the minister said. If we assume that all of these people did indeed have COVID-19 then Kyrgyzstan’s coronavirus death statistics would be doubled in one fell swoop.

(Since this article was originally published, the situation has only got worse, with tens of pneumonia deaths https://en.fergana.ru/news/119798/?country=kg not officially ascribed to the coronavirus being recorded each day. By 3 June, the number of such “non-COVID” pneumonia deaths since March had already risen to 120 – ed.).

Overburdened

There is nothing especially surprising or contrary to science in any of this. No one ever claimed that PCR tests were 100% reliable. Epidemiologist Mikhail Favorov, who works in the US, stated in an interview with the Ukrainian news agency UNN: “I am positive towards PCR tests, but we need to know their limits. PCR tests need to be carried out in certified accredited laboratories.” Favorov explained that at the start of the pandemic, there was no possibility of carrying out more reliable antibody tests, so laboratories all over the world had to quickly implement PCR testing and conduct analyses on a massive scale. This led to a sharp drop in the quality of diagnostics. In addition, at the very peak of the illness, if a person has a lot of antibodies, PCR tests may fail to detect the virus – since it is being destroyed by the antibodies. Ultimately, everything is a lot more complicated than just a matter of a single test being able to determine the presence or absence of the coronavirus.

Kyrgyz doctor Omor Kasymov, too, has argued that the focus on PCR testing can be seen as underreporting the scale of the epidemic. “PCR tests are viewed as a rather reliable method, but right now there are a large number of false negatives. When someone is ill they are producing a lot of antibodies, reactions are going on, and at this stage of the illness you can easily get false negatives,” he explained. Kasymov said that all cases with COVID-19 symptoms should be included in the statistics regardless of the results of PCR tests.

On the other hand, in one sense it is unimportant to Kyrgyz doctors and patients whether an illness is officially classified as pneumonia or the coronavirus. What is important is that hospitals are not overfull. This point has been made not only by the late Elakunov, but also by many other patients and medical workers. Sources in Bishkek’s Clinical Hospital No.1 recounted that on 27 June they set aside 80 beds in the hospital for pneumonia patients, but already by 29 June they had had to find space for 90 patients. Four people passed away there in 24 hours. Teams of two doctors and two nurses take it in turns to replace each other in 8-hour shifts, meaning that just four people have to take care of 90 severely sick patients. Meanwhile, on 29 June a Bishkek resident by the name of Artyom told journalists that he had been unable to get his elderly father hospitalised for ten days already. “Today a team from the 118 service (Kyrgyzstan’s coronavirus hotline – ed.) came and carried out some tests, checked his lungs with a stethoscope and said: you have had double pneumonia for around a couple of days already. We can’t take you in to hospital, everywhere is full, you’ll have to recover at home, they said. They gave us instructions for how to take care of him. We’ve done this, but it’s not getting any better,” he said anxiously.

Meanwhile, two men died just outside of the entrance to the Urology Centre in Bishkek, where extra beds have been set up for pneumonia patients. Relatives had managed to drive them up to the hospital building, but it was already too late to take them inside – medics tried and failed to resuscitate them as they lay one on the pavement and one in the back seat of a car. Head doctor Tilek Umetaliev explained that the reason for the tragedy was that relatives had failed to seek medical help in time. What he did not explain was how it is possible to be “in time” in the conditions described above by Artyom and by a multitude of other Kyrgyz citizens on social media who complain of the difficulty of obtaining medical care.

Until recently, the health ministry denied that any such issues even existed, but on 30 June the deputy head of the agency, Madamin Karataev, acknowledged that: “One of the main problems at present is a lack of hospital beds, especially in Bishkek and Osh. There has been a sharp rise in the number of severe pneumonia patients.” And the day before, the health ministry, while not lending direct support to the idea that PCR test results were unreliable, nevertheless decided to hospitalise some groups of patients without waiting to conduct tests. Now people with severe and moderately severe pneumonia, people with COVID-19 symptoms over 60 years old, and also those who are unable to isolate themselves at home should be taken directly to hospital. Against the background of everything mentioned above, however, the question remains – to which hospitals? By which ambulances? To be treated by which medics?

Within the constraints of its limited resources, the ministry is now trying to respond to the deteriorating epidemiological situation. Additional beds are being set up at secondary hospitals. 20 extra ambulances have been brought into service – 15 of them were previously impounded as part of criminal investigations into irregularities committed during their purchase, and another five have been made available by the State Committee for Defence Affairs. Finally, 870 reserve medics (including medical students) have been mobilised. On 30 June they began a short five-day preparation course for the fight against COVID-19.

Meanwhile, the head doctor at the disease control department in Osh, Saltanat Orozbaeva, complained to journalists that her office had began to run out of the vials needed to conduct COVID-19 tests on 28 June. As a result they started to test only severely ill patients. Orozbaeva appealed to Osh mayor Taalaybek Sarybashov and the government’s Osh region representative, Uzarbek Jylkybaev. But even they were unable to resolve the issue. “They even called Uzbekistan,” Orozbaeva said. In the end, a batch of vials were found somewhere in Bishkek and, as of 30 June, they have promised to forward them to Osh.

A touch of politics

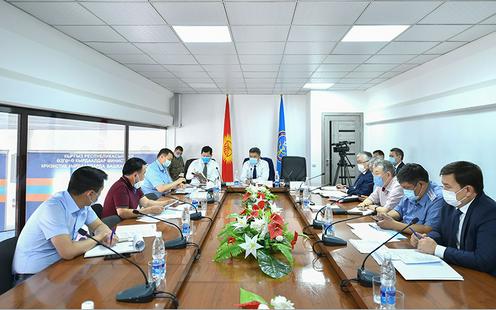

COVID-19 is being detected en masse in many of the country’s foremost institutions. Positive test results have been returned by a number of deputies in the Jogorku Kengesh (parliament), by employees of the Central Electoral Committee and the Central Bank, and by Bishkek mayor Aziz Surakmatov himself. But Kyrgyzstan’s stormy political life cannot so easily be brought to a halt. On 15 June, Prime Minister Mukhammedkaliy Abylgaziev resigned, having been accused by one MP of participating in the corrupt sale of the country’s airwaves. Abylgaziev’s position as PM was taken over by Kubatbek Boronov. Following the Jogorku Kengesh’s confirmation of Boronov in the post, the whole government, plus both the former and new prime ministers, decided to eternalise the moment with a group photo. The photo provoked a storm of indignation on social media, though, since, of the hundred or so individuals pictured standing shoulder to shoulder, several rows deep, only one person was visible wearing a face mask.

Social media users supported President Sooronbay Jeenbekov when he announced that the entire government was to be fined for violating quarantine regulations. And they were indeed made to pay a fine of 140,000 soms ($1,900) each. 26 employees of the government offices soon tested positive for the coronavirus. Whether they were among those pictured in the infamous group photo, however, remains unknown.

At the same time, it should not be forgotten that Jeenbekov himself has been repeatedly criticised for appearing at various events without a mask. The presidential press service has explained that, rather than wear a mask, he makes sure to maintain a social distance.

On 24 June, Jeenbekov was scheduled to take part in the Victory Day Parade in Moscow – Russian president Vladimir Putin felt that, compared to the original date of 9 May, the epidemiological situation in the country had stabilised to such an extent that it was now possible to go ahead with the previously-cancelled celebrations. Interestingly, on the very same day, a court in Bishkek sentenced Jeenbekov’s political rival, ex-president Almazbek Atambaev, to 11 years and two months in prison. The former head of state was found guilty of orchestrating the illegal release from prison of crime boss Aziz Batukaev. Jeenbekov probably felt it necessary to distance himself from the case and verdict as much as he possibly could. While Atambaev’s supporters were busy expressing their indignation over the sentence, the current president and his team landed two thousand miles away in Moscow. Yet in TV broadcasts of the Red Square parade he was nowhere to be seen. It soon emerged that two members of the Kyrgyz delegation had tested positive for COVID-19 and Jeenbekov’s participation in the event had therefore had to be cancelled.

On returning to Kyrgyzstan, the two infected officials were sent off to recover at home, since they only had mild forms of COVID-19. The remaining members of the delegation, including Jeenbekov, were placed in home isolation. Already on 30 June, however, the president was once again present in the Jogorku Kengesh to receive the oaths of the members of the new government (though these were exactly the same ministers as before, just under the leadership of Boronov and not Abylgaziev). It was announced that two PCR tests had failed to detect any sign of the infection in the head of state. No one paid any attention to the possibility of obtaining false negatives, nor to the fact that the incubation period of the virus can be up to 14 days, during which time a person may remain infectious. Jeenbekov did in fact arrive at the session wearing a face mask, but he then removed it and spent the next 50 minutes at the podium entirely free of any kind of protective gear.

This notwithstanding, a large part of the president’s speech was devoted to both the rise in infection numbers and widespread failure to observe anti-epidemiological measures. Jeenbekov declared that the state of emergency had been lifted in order to keep the economy alive, yet many people had taken it to mean the total withdrawal of any kind of restrictions. As a result, all of the successes achieved during the state of emergency and accompanying strict lockdown could soon become undone. “Unfortunately, sanitary-hygienic regulations are not being observed in public places, at industrial enterprises, on public transport and in major shopping centres. Traditional celebrations, toys (celebratory feasts) and other events involving large numbers of people are once again being held,” the head of state complained. He then stressed: “This shows a lackadaisical attitude to the efforts of our doctors, our law enforcement officers and other state employees who have been working since March without rest and without sleep, day and night standing guard over the health and wellbeing of the nation!”

Jeenbekov added, however, that there will be no immediate return to a strict general lockdown. “If we show a high level of civic responsibility, maintain order and discipline and do not violate medical regulations, then we can emerge from this test with our heads held high,” he promised.

On the very same day, 30 June, news arrived from the detention facility run by the State Committee for National Security that Atambaev had been diagnosed with double pneumonia. A PCR test came back negative. The former president was transferred from his detention cell to a hospital and an argument promptly broke out between Atambaev’s family and lawyers on the one hand, and the SCNS on the other, about just who was to blame for his COVID-19 infection (which, according to PCR tests, does not exist). Atambaev’s relatives insist that the ex-president may have been deliberately infected in the hope that he would die. The SCNS responded that family members themselves had been meeting with Atambaev over the previous week and passed on a number of items and objects to him in person. The security forces also allege that one of the detainee’s lawyers, Zamir Jooshev, too has developed coronavirus symptoms. (Since this article was originally published, Atambaev’s son Seid, himself active in politics, has also been hospitalised with pneumonia – ed.). Meanwhile, Atambaev’s second lawyer, Sergei Slesarev has been unsuccessfully trying to access the ward where his client is currently undergoing treatment.

Everything gets mixed up

In the first months of the epidemic, while the country was placed under a strict quarantine, something similar happened with the flow of information. It was possible to talk of the danger posed by the new illness (which then seemed to be a highly theoretical and even contested question) as a distinct topic, and then go over to discussing the catastrophic economic and social consequences of the lockdown – and of course to attempt to predict the effect they may have on the balance of political power. Now such a division is no longer possible. PCR tests, earlier taken as a kind of “magic wand” to distinguish the healthy from the sick, have not lived up to expectations. It has similarly not been possible to divide up time into “the period of the lockdown” and “normal life” either.

At present in Kyrgyzstan there is no separate Atambaev-Jeenbekov rivalry – there is only the rivalry of the Atambaev who has been diagnosed with double pneumonia and Jeenbekov, the man who does not pay much attention to requirements to self isolate. There is no separate topic of Abylgaziev’s resignation (which analysts had been predicting for around a year). There is only the news jumble of his resignation together with the controversial photo with the non-existent social distancing and the positive test results of a number of government officials. There was no separate ratification of the contentious law “On the manipulation of information” – instead there was a furore over voting carried out “on the sly” while many deputies were at home in self-isolation. And then there is the protest march against the new law, which can easily be seen as a highly undesirable mass public event given the present circumstances.

But the most important thing is that now no one in Kyrgyzstan can claim that he and his family have been left broke as a result of unjustified restrictions introduced by the government. True, he may have lost his income, but the alternative is now clear – not a normal continuation of his professional life free from all interference, but possible death by asphyxiation in an overcrowded hospital. The saddest thing of course is that people now face the danger of a loss of earnings and a loss of life together. On the other hand, even if the restrictions are lifted, the restoration of financial stability is a far from straightforward task. A clear example of this is the position in which the owners of bed and breakfast establishments around Issyk-Kul have found themselves. There is no ban on them accepting guests, but no foreign tourists are visiting the area on account of the closed borders and no Kyrgyz are doing so due to a lack of money. Meanwhile the owners of private kindergartens, permitted to reopen back in June, have found that few people are keen to give up their children into their care, while the authorities are more than eager to hand out fines for alleged infringements of anti-epidemiological regulations.

Labour migrants who have lost their jobs in Russia and done all they can to make it back home, too, have found themselves in a precarious position. As is clear from the testimony of the State Migration Service and of members of the diaspora themselves, many migrants have now realised that there is no work for them in Kyrgyzstan either. Some of them have already started, unsuccessfully, looking for ways to make it back into Russia. At the same time, other Kyrgyz citizens who remain abroad continue to fill up charter flights home.

There are few people left now who continue to have faith that COVID-19 will somehow disappear in the autumn. On the contrary, there is a very high probability that the coronavirus, like all other viral respiratory infections, is only going to increase in strength in cold weather. The “introduce a lockdown, wait it out, and then return to life as normal” plan can be considered to have well and truly failed. Kyrgyz citizens, like the citizens of all other countries around the world, will have to learn to live with this illness for some time yet to come. And exactly how their lives will be affected over this long-term perspective – this remains unclear.

Tatyana Zverintseva

Translated and updated by Nick L.

-

24 December24.12To Clean Up and to ZIYAWhat China Can Offer Central Asia in the “Green” Economy

24 December24.12To Clean Up and to ZIYAWhat China Can Offer Central Asia in the “Green” Economy -

23 December23.12PhotoTokyo DriveJapan to invest about $20 billion in projects across Central Asia over five years

23 December23.12PhotoTokyo DriveJapan to invest about $20 billion in projects across Central Asia over five years -

17 December17.12Sake for SixCentral Asia’s Rapprochement with Japan Comes with Hidden Pitfalls

17 December17.12Sake for SixCentral Asia’s Rapprochement with Japan Comes with Hidden Pitfalls -

15 October15.10A Step Back into the Middle AgesWhy Kyrgyzstan Should Not Reinstate the Death Penalty

15 October15.10A Step Back into the Middle AgesWhy Kyrgyzstan Should Not Reinstate the Death Penalty -

17 September17.09Risky PartnershipWhy Dealing with China Is Harder Than It Seems at First Glance

17 September17.09Risky PartnershipWhy Dealing with China Is Harder Than It Seems at First Glance -

04 July04.07Which Patch Did You Trample?Those Wishing to Join Kyrgyzstan’s Political Life Risk Criminal Records

04 July04.07Which Patch Did You Trample?Those Wishing to Join Kyrgyzstan’s Political Life Risk Criminal Records