Over the past month, Kazakhstan’s President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev—who has repeatedly advanced various environmental initiatives and once even launched the campaign “Taza Kazakhstan” (“Clean Kazakhstan”)—has twice raised the issue of the current state of the Caspian Sea, at both the SCO summit and the UN General Assembly. The Kazakh leader’s concern is welcome, especially against the backdrop of the general passivity of the Caspian littoral states, which seem more focused on exploiting the economic potential of the dying sea than on preventing an ecological disaster so vast that, by comparison, the Aral’s demise would appear a local emergency.

Analogies with the Aral are obvious even to an outside observer. Even Russian President Vladimir Putin—whose attention to environmental issues is clearly peripheral under the current geopolitical agenda—remarked at the end of last year, speaking at the International Congress of Young Scientists:

“We must by no means allow [with the Caspian] what happened to the Aral Sea. There it is all salt, only puddles remain. I don’t know if we, even by joining forces, can do anything, because nature is a powerful system. Nevertheless, everything that depends on us, we must do.”

It is quite possible that Putin was influenced by his visit to Baku in August 2024, when Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev gave him the chance to see firsthand what is happening with the Caspian Sea. Aliyev recalled:

“From the window of the room where we held talks, I showed Vladimir Vladimirovich the rocks that two years ago were still under water, but today have risen a meter above the surface. And this we are observing along the entire coastline.”

The undertones of fatal inevitability in the words of both Putin and Aliyev are troubling enough. But even more troubling is the inaction of the authorities of all five Caspian littoral states, who so far are merely recording the sea’s tragic decline when the situation demands not words but action.

What the Sea Means

The importance of the Caspian Sea—a vast body of water larger in area than Germany and more than a kilometer deep—for the countries that share its shores is hard to overstate. Drawing parallels with the Aral, whose disappearance was an ecological disaster but largely a regional one, is not easy in this case. The Aral was six times smaller in area and, unlike the Caspian, did not provide transport and trade links (north to south and east to west), serve as a major site of hydrocarbon extraction, or function as a corridor for their delivery.

On the “North–South” route alone, cargo traffic on the Caspian has risen in the past three years from 16.3 million to 26.9 million tons. That is roughly the same volume carried annually by rail between Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. This year, the total cargo turnover of Caspian ports is expected to reach 28–30 million tons, and by 2030 to climb to 35–50 million. For comparison, in the Aral’s best years only about 250,000 tons of goods of all kinds were shipped.

The largest town on the vanished Aral’s shores was Aralsk, with a population of a few tens of thousands. On the Caspian, however, lie Baku (2.5 million residents), Makhachkala (670,000), Sumgait (350,000), and Aktau (270,000). Astrakhan and Atyrau, though slightly upstream on the Volga and Ural rivers that flow into the Caspian, are directly affected by the sea’s decline. Thus, the post-apocalyptic landscapes of today’s Aralsk and Muynak, under the most pessimistic scenario, may soon become a familiar sight for millions of people in the Caspian littoral states.

The Caspian is ringed mostly by arid and semi-arid regions, yet along its shores one can still find a striking variety of ecosystems, from wetlands to sandy beaches. Its natural wealth, beyond the vast oil and gas reserves (estimated at 12–22 billion tons of oil equivalent on the Caspian shelf), also includes salt and fish. Even with the decline of its fauna, up to 150,000 tons of fish are still caught here annually (in the Aral before the 1960s, annual hauls never topped 50,000 tons). And if fish are growing scarcer, salt will only increase as the sea continues to shrink—though that prospect is unlikely to please anyone.

The Caspian’s resources have played a central role in the global economy for centuries. But in recent decades, disputes over their extraction and use have consistently blocked coordinated steps to save the sea. Each littoral state continues to exploit its own fisheries or offshore fields, confining itself to statements of “serious concern” or diplomatic bustle at international forums.

Quantity and Quality

Here it is worth pausing to look more closely at what lies behind the “degradation” mentioned above—and, at the same time, to explain why Kazakhstan’s president is so concerned. His alarmist message before the U.N. General Assembly, notably, was echoed by Ilham Aliyev.

The most immediate worry is the Caspian’s falling water levels. The world’s largest lake has always been highly unstable, and this trait gives some observers reason for undue optimism: water levels have dropped before, they argue, so we are merely waiting for another cycle to end. In this sense, global warming and the Caspian’s retreat are phenomena of the same order. First, they are directly linked: there is less precipitation, and evaporation is greater. Second, belief in them is uneven: some accept them as fact, others dismiss them—though confidence in the skeptics is waning, especially after pronouncements like Donald Trump’s talk of a “new green scam.”

That said, history and direct observation both show the Caspian undergoing sharp long-term and shorter fluctuations in level, driven by complex interactions of climate and river inflow—chiefly from the Volga. The Volga accounts for 80 percent of the Caspian’s river inflow, and that in turn supplies about 80 percent of the sea’s overall water balance (the other 20 percent comes from atmospheric precipitation and groundwater flow through aquifers).

At different points in history, the gap between minimum and maximum levels has exceeded 15 meters; in the distant past, it reached 50 meters or more, especially during major transgressions such as the Khvalynian, about 13,000–18,000 years ago. Over the last two millennia, fluctuations have also surpassed 15 meters, with periods in which the rate of change reached as much as 14 centimeters per year.

In the 20th century, fluctuations were on average less dramatic but still noticeable—about three to four meters over the course of the century. But from 1995 to 2024, the water level dropped by three meters, with the rate of decline reaching 30 centimeters per year in 2021–22. According to the latest data, the Caspian has already fallen to about –29.5 meters below sea level, lower than the historic minimum of –29.01 meters recorded in 1977.

This brings us back, inevitably, to the Volga—a river heavily regulated by dams and equally affected by climate change. Its 2019 low was described by experts as a “true ecological catastrophe,” forcing water-rationing measures across the entire cascade of hydroelectric plants. Two years later, the Kuibyshev Reservoir, the largest in the Volga basin, reached a critically low mark. It seemed the bottom had been hit, but in 2023 water levels dropped further still.

On many stretches, navigation ceased altogether, and by year’s end the Volga’s total discharge was only 80 percent of the norm—the lowest in 25 years. In 2025, after a snow-poor winter, residents of the upper Volga regions—Tver, Yaroslavl, Nizhny Novgorod—again discovered, with astonishment, that their beloved river had retreated tens of meters from its banks, exposing a littered bed.

The reasons for the Volga’s decline are a story in themselves, but in short, precipitation is only part of it. Other fundamental factors are at play: damming, siltation, deforestation, increased evaporation surface, and reduced flow velocity. For now, no serious effort is being made to address these issues, so there is little reason to expect the river to suddenly begin delivering its former volumes of water to the Caspian. Yet in his remarks at the United Nations, Ilham Aliyev emphasized precisely the anthropogenic nature of the Caspian’s problems.

The situation with the Caspian’s other tributaries is no better than with the Volga. Kazakh environmentalists have long been sounding the alarm over the shallowing of the Ural (Zhayyq), and only this year, thanks to a snowy winter, did the water level rise. Meanwhile, reports from Azerbaijan speak of a decline in the Kura, and in Dagestan they talk about the “abnormal shallowing” of the Terek.

But it is not only the quantity of water in the Caspian that is cause for concern—the quality has been deteriorating as well, with predictable effects on the sea’s biodiversity. Pollution from oil and industrial waste, both discharged directly from the shores and carried in by rivers from the entire Caspian basin—a region of some 3.5 million square kilometers with a population of 120–130 million—has reached staggering proportions. By some estimates, the sea receives 120,000 tons of oil products every year—the equivalent of 2,000 railroad tank cars. In addition, industrial and sewage discharges bring phenols, heavy metals such as mercury, chromium, and nickel, as well as fertilizers and pesticides. Fifteen years ago, researchers in Iran calculated that each year the Caspian receives 300 tons of cadmium and 34 tons of lead, while the total volume of wastewater was measured in the tens of billions of cubic meters.

With such “nutritional supplements,” the living conditions for marine life are deteriorating rapidly. Sturgeon have nearly disappeared from the Caspian; seals are dying in the thousands; and dozens of endemic fish and mollusk species found nowhere else in the world are under threat. Even the fauna of the Aral did not collapse so badly until the sea itself began to shrink. And yet it too received its share of pollutants carried by the Amu Darya and the Syr Darya.

Life According to Pessimists

Contrary to the widespread belief that the era of geographical discoveries is long past, in 2024 scientists exploring the northern Caspian unexpectedly found a new island. For now, it rises only 30 centimeters above the water, but it is clear that with time it will become more “mountainous.”

As Professor Andrei Kostyanoi, Doctor of Physical and Mathematical Sciences and chief researcher at the Russian Academy of Sciences’ Institute of Oceanology, explained:

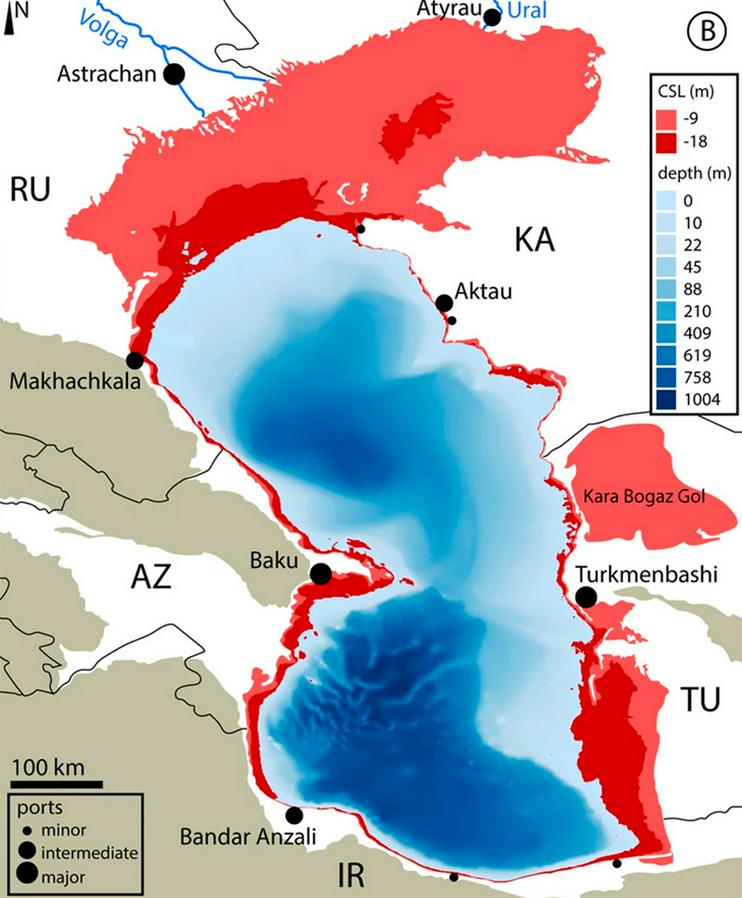

“This [drop in sea level] is occurring evenly across the entire basin, but the most visible effects are in shallow areas with gently sloping bottoms. These include virtually all the shores of the northern Caspian—both in Russia and Kazakhstan. Here, the sea has retreated anywhere from several kilometers to several dozen.”

In other words, it is the residents of the Kazakh and Russian parts of the Caspian who should prepare first: if the current pace of shallowing continues, by 2030 the sea will retreat another several dozen kilometers. Even in Azerbaijan, however, 400 kilometers of seabed have been exposed in just the past five years.

According to reports in several Kazakh media outlets this August, since 2006 the sea has retreated from its former shoreline near Aktau by 18 kilometers. Another stark example of the Caspian’s degradation lies on the Russian coast—or rather, used to. The town of Lagan, founded in the second half of the 19th century on an island once surrounded on all sides by Caspian waters, now sits more than ten kilometers inland. Once renowned for its rich fish catches, Lagan has seen its fish-processing plant converted into a meat factory, its former port filled with the rusting skeletons of ships, and its lighthouse reduced to ruins.

Meanwhile, scientists looking further ahead sketch a picture of full-scale catastrophe. By the end of this century, they project, the level of the Caspian could fall by 9 to 18 meters, shrinking its surface area by a third. The northern Caspian and Turkmen shelves, as well as coastal regions in the middle and southern Caspian, would be laid bare, while the Kara-Bogaz-Gol bay on the eastern shore would vanish entirely. The Volga, Ural, and other rivers would thread their way across the former seabed—now desert—to what remained of the sea, hypersaline and choked with human waste.

Living by such a body of water would be anything but comfortable—after all, there are few eager to settle on the shores of the Great (Southern) Aral. And for good reason: in the zone of ecological catastrophe, rates of cancer, respiratory diseases, neurological and digestive disorders, and congenital defects among children rose sharply compared with other regions of Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan.

If the scenarios outlined by scientists come to pass, there will be no ice or seals left in the Caspian, and only fish able to adapt to highly mineralized water will survive. Worse still, one can hardly imagine the clouds of sand that winds would lift from the exposed seabed and carry for thousands of kilometers across Eurasia.

Alongside dwindling fish stocks and worsening living conditions on the Caspian coast, the sea’s retreat will, however, create new opportunities for oil producers: pumping “black gold” from the exposed seabed—though not transporting it—will become much easier. Nevertheless, the overall crisis in the Caspian region could trigger fresh disputes among neighboring countries, especially if anyone seeks to push for changes in territorial boundaries, internal waters, fishing zones, or national sectors of the seabed.

Despite all this, some remain optimistic, continuing to emphasize the cyclical nature of changes in the Caspian basin—though such hopeful voices are becoming increasingly rare. For example, former Russian Minister of Natural Resources and hydrologist Viktor Danilov-Danilyan even engaged in a remote exchange of views with the President of Azerbaijan:

«By his speech at the UN on the allegedly anthropogenic causes of Caspian shrinkage, Ilham Aliyev tried to spread responsibility and blame for environmental degradation across all coastal countries, even though Baku itself makes a massive contribution to polluting the sea… In reality, the water level in the Caspian Sea depends at least 80% on the flow of the Volga, which is itself a cyclical process. It has been changing for several millennia for reasons unknown to scientists and is practically unrelated to anthropogenic factors… Climate change is not the cause of this cyclicality, although it can certainly exacerbate the situation."

Danilov-Danilyan is confident that the periods between peak Volga flows last 40 to 60 years; therefore, by 2040–2050, the situation in the Caspian could completely reverse, and its level could start rising again—assuming, of course, that human activity and the climate changes it triggers do not push the next cycle into a steep decline. Or perhaps they already have.

What Can Be Done?

«The Caspian Sea is rapidly shrinking. This is no longer just a regional problem; it is a global warning signal,» Kazakh President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev said at the UN. «Therefore, we call for urgent measures to preserve the Caspian’s water resources in cooperation with our regional partners and the entire international community."

The question arises: what measures could be taken? And is it even too late to act? The answer to the second question is simple—no, it is not too late. Even if those who share Danilov-Danilyan’s perspective—arguing that the current cycle might pass without catastrophe—are correct, it is clear that the sea is in distress. Humans must not only urgently work to restore it but also be prepared in case intervention proves insufficient.

The answer to the first question must come from the Caspian littoral states themselves—but only if they coordinate their efforts and agree to act as a unified front. Ideally, this should happen under some form of international supervision. So far, each country pursues its own environmental initiatives, which, frankly, inspire little confidence.

Of course, it would be naïve to expect Russia to simply blow up its dams and let the Volga’s waters flow freely southward—such a move alone would hardly solve the Caspian’s problems. On the contrary, it could trigger a large-scale ecological disaster with enormous long-term damage to the region’s environment, economy, and population.

Instead, the Caspian littoral states could:

▪️ exercise strict control and regulation of water withdrawals from rivers feeding the sea;

▪️ expand the boundaries of water protection zones along the coast;

▪️ implement advanced technologies for treating domestic and industrial wastewater everywhere;

▪️ organize continuous ecological monitoring of water levels and quality;

▪️ enforce mandatory international environmental standards for the oil and gas sector;

▪️ more actively launch ecosystem restoration projects; and finally—

▪️ impose massive fines on those who violate environmental standards. These penalties should be maximized and applied simultaneously across all Caspian states.

At the same time, it would be beneficial to involve the world’s leading experts to identify the causes of the Caspian’s ecological degradation, monitor the sea’s ecosystem, and develop recommendations for its restoration. And, of course, the region’s population should be continuously educated in basic environmental literacy.

For now, efforts to combat the sea’s shrinking and pollution are largely limited to numerous ceremonial events and the protocols adopted following them—but as the sea’s condition shows, all these symbolic measures do little for the Caspian. Even simple private initiatives, such as cleaning up litter along the shore, installing water-saving faucets, or watering gardens only in the evening (when evaporation is minimal), appear in the long term to be more effective than the current state policy toward the planet’s ancient sea. Homer once called it “a pond from which the sun rises every morning.” Let us hope it does not ultimately become just a pond.

Pyotr Bologov

-

24 December24.12To Clean Up and to ZIYAWhat China Can Offer Central Asia in the “Green” Economy

24 December24.12To Clean Up and to ZIYAWhat China Can Offer Central Asia in the “Green” Economy -

23 December23.12PhotoTokyo DriveJapan to invest about $20 billion in projects across Central Asia over five years

23 December23.12PhotoTokyo DriveJapan to invest about $20 billion in projects across Central Asia over five years -

17 December17.12Sake for SixCentral Asia’s Rapprochement with Japan Comes with Hidden Pitfalls

17 December17.12Sake for SixCentral Asia’s Rapprochement with Japan Comes with Hidden Pitfalls -

24 November24.11Here’s a New TurnRussian Scientists Revive the Plan to Irrigate Central Asia Using Siberian Rivers

24 November24.11Here’s a New TurnRussian Scientists Revive the Plan to Irrigate Central Asia Using Siberian Rivers -

22 October22.10Older Than the Eternal CityWhat has Samarkand accomplished in its three thousand years of existence?

22 October22.10Older Than the Eternal CityWhat has Samarkand accomplished in its three thousand years of existence? -

16 October16.10Digital Oversight and Targeted RecruitmentRussia Approves New Migration Policy for 2026–2030

16 October16.10Digital Oversight and Targeted RecruitmentRussia Approves New Migration Policy for 2026–2030