A contemporary art museum — the Almaty Museum of Arts, founded by businessman and patron Nurlan Smagulov — has opened at the intersection of Al-Farabi and Nazarbayev avenues in Almaty. The event marks a new chapter not only in the cultural life of Kazakhstan’s southern capital but for the entire region.

Fergana spoke with art critic Valeria Ibraeva about why this is important, how the idea for the museum came about, and whose works are on display.

— Have there previously been similar museums in Kazakhstan or other Central Asian countries?

— Until the event on September 9 (the “pre-opening” of the new museum in Almaty for officials and journalists — Editor’s note, Fergana), there were no museums of contemporary art in Central Asia. Moreover, during the Soviet era, across the vast territory of Kazakhstan there were only seven fine arts museums. With independence, two more were added — state art galleries that “grew” into museums. These showcased historical painting, from 1934 onward, and up to more recent works, but without the flavor of what we now call contemporary art.

The fundamental difference between a contemporary art museum and a classical one lies in the fact that it exhibits, documents, and studies art created in the past thirty years — art that responds to life as it unfolds. As we know, Socialist Realism produced an illusory world, whereas the value of contemporary art is in its examination of real life, with all its strengths and shortcomings.

— How much time passed between the birth of the idea and the opening of the museum?

— In principle, any collector, from Tretyakov to Guggenheim, begins by gathering works, keeping them at home, admiring them. Then the collection grows, and the natural outcome for such a collector is the desire to build a museum. Most museums, including, for instance, the Louvre, originated from private collections.

I believe this idea came to Nurlan Smagulov a long time ago, about twenty years back, while the museum’s cornerstone was laid in 2021. Some works Nurlan bought from the Kazakh collector Yuri Alekseyevich Koshkin, who also dreamed of opening a museum and even rented a building for it. But in the 1990s, there was neither equipment nor a strong concept — he simply hung the paintings and called it a museum.

Now everything is happening at a completely different level. The museum building was designed specifically for exhibiting contemporary art. Its functions differ from those of a classical museum, since there are many technical challenges and very complex storage requirements. All of this has been done very professionally, at the level of global museum management.

— Whose works are on display, which ones stand out, and what idea unites the exhibition?

— First of all, there are large halls dedicated to world contemporary art classics such as Yayoi Kusama, Anselm Kiefer, and Bill Viola, whose works are shown in museums all over the world.

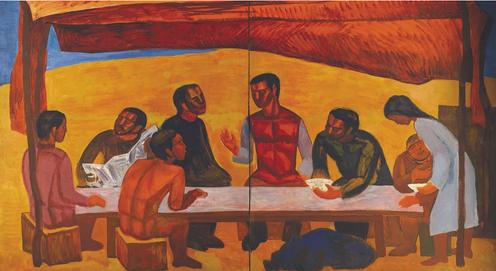

The Kazakhstan section features two exhibitions. One is called Қонақтар (Konaktar), which means “Guests” in Kazakh — it is a collection from Nurlan Smagulov, the museum’s founder. The exhibition was curated by Inga Lace, who came to us from Latvia, which we are very happy about because she has a fresh, unjaded eye. She created a show exploring how traditions of hospitality are used in contemporary life. For example, it includes a 1970s work by Salikhitdin Aytbaev — one of the versions of Tractor Drivers’ Supper. The characters offer each other a seat, demonstrating genuine hospitality.

There are also works dedicated to migration. In Kazakhstan, various types of migrants exist, such as kandasy — blood relatives, Kazakhs who returned from Afghanistan, Mongolia, and other countries — as well as labor migrants. Recently, as you know, many migrants from Russia have arrived, though they have yet to appear in art.

This is the first exhibition representing all Kazakh art from the 1960s–70s up to the most recent works, such as those by Dili Kaipova, featuring Arabic inscriptions, and Yerbossyn Meldibekov, who depicts mountain peaks as crumpled plumbing — a very witty approach.

Announcement of Almaguul Menlibayeva’s exhibition featuring her work Journey in an Orange Dream, 1988. Screenshot from almaty.art

Announcement of Almaguul Menlibayeva’s exhibition featuring her work Journey in an Orange Dream, 1988. Screenshot from almaty.art

The museum also hosts a solo exhibition by Almaguul Menlibaeva, born and raised in Almaty. It is a retrospective featuring her early works, purchased by local collectors, up to the present. The exhibition covers not only painting but also video and montage, making it a multifaceted and technically diverse display.

As our art develops and reaches the international stage, Almaguul Menlibaeva has moved to Berlin and Brussels, where she works successfully — an achievement we are very proud of.

— Which Kazakh artists are currently known internationally besides Menlibayeva? Can we say that Kazakh contemporary art is gradually entering the global market?

— I won’t talk much about painters, because we are primarily discussing contemporary art, and experiments in painting are quite challenging for a modern artist due to the weight of traditions (socialist realism, and so on). Mostly, we have installations, sculptures, and photographic works. I personally organized several exhibitions in Italy, as well as the first exhibition of contemporary Central Asian art in Berlin, at the House of World Cultures in 2001. (Valeriya Ibraeva headed the Soros Center for Contemporary Art in Almaty for over ten years — ed. Fergana).

If we name some artists, these are our stars — Erbosyn Meldibekov, Said Atabekov, Saule Dyusenbina, Elena and Viktor Vorobyev, Saule Suleimenova, Kuanish Bazargaliev — a fairly large, compact group that has exhibited worldwide. I can honestly say that they create art that is quite interesting for the global stage.

As for gradually entering the market — this didn’t start just now. We have been on the map of the contemporary global art scene for about ten years, and of course, we don’t play first fiddle there, but somewhere out there we are striking the triangle.

— Almost simultaneously with Nurlan Smagulov’s museum in Almaty, the Tselinny Center for Contemporary Culture opened. Won’t they compete?

— Tselinny is also a huge building, and it was also built by a wealthy billionaire (the well-known oligarch Kairat Boranbayev — ed. Fergana). It’s very important that the museum and the center opened almost at the same time, because the museum’s task is to preserve, study, and exhibit artworks — works that have been tested by time. They should participate in exhibitions, galleries, biennales, and then be archived in the museum. The Center for Contemporary Culture, on the other hand, is aimed at directly supporting the artistic process. Its task is not to preserve, study, or exhibit, but to create and drive the artistic process forward. This is a very successful tandem. We hope that having these two large institutions will elevate our art scene to unprecedented heights.

-

05 February05.02The “Guardian” of Old Tashkent Has Passed AwayRenowned local historian and popularizer of Uzbekistan’s history Boris Anatolyevich Golender dies

05 February05.02The “Guardian” of Old Tashkent Has Passed AwayRenowned local historian and popularizer of Uzbekistan’s history Boris Anatolyevich Golender dies -

23 December23.12PhotoTokyo DriveJapan to invest about $20 billion in projects across Central Asia over five years

23 December23.12PhotoTokyo DriveJapan to invest about $20 billion in projects across Central Asia over five years -

17 December17.12Sake for SixCentral Asia’s Rapprochement with Japan Comes with Hidden Pitfalls

17 December17.12Sake for SixCentral Asia’s Rapprochement with Japan Comes with Hidden Pitfalls -

24 November24.11Here’s a New TurnRussian Scientists Revive the Plan to Irrigate Central Asia Using Siberian Rivers

24 November24.11Here’s a New TurnRussian Scientists Revive the Plan to Irrigate Central Asia Using Siberian Rivers -

11 November11.11To Live Despite All HardshipUzbek filmmaker Rashid Malikov on his new film, a medieval threat, and the wages of filmmakers

11 November11.11To Live Despite All HardshipUzbek filmmaker Rashid Malikov on his new film, a medieval threat, and the wages of filmmakers -

22 October22.10Older Than the Eternal CityWhat has Samarkand accomplished in its three thousand years of existence?

22 October22.10Older Than the Eternal CityWhat has Samarkand accomplished in its three thousand years of existence?